Step into the future, it’s waiting for you

When I pitched this piece about North East England, the first three sentences were: “I don't want to write about coal mining. I don't want to write about ship building. I want to write about shopping.”

But the first part is all about coal mining. I’m sorry. I tried to keep it brief.

The second part is all about suspended ceilings – those grids and tiles you find in offices and shops. People use them as shorthand for drudgery. There was a lot more about ceilings in my early drafts. I’ve cut most of it out. You’re welcome.

The final part is about grout and the future. I’ve a good story about grout. I’ve got no stories about the future.

But it starts with Sir John Hall, former owner of Newcastle United. He phones when I’m on my way to Asda. He received my email. He says he wanted to write a book about the Metrocentre himself but never did and I can use his documents if I want.

I can’t go to his house though, he says, because of Covid. A few days later, he phones again and says I can go to his house as long as I keep my distance. So I put the kids in the car and drive up into Northumberland and through his gates.

He comes out of the garage. He’s 87 years old. We stand a few metres apart and talk. He puts a blue Aldi bag on the driveway.

“It’s all in there,” he says.

A week later I interview him on the phone.

A week after that he phones back, worried.

John: “It’s not about me is it?”

Me: “No.”

John: “It’s about the Metrocentre?”

Me: “Yes.”

John: “Good.”

Me: “Why?

John: “Because I’ve had enough.”

It’s not about him. He’s told his story many, many times, and if you look through the cuttings you can see the edges being smoothed away by journalists over the years. So I won’t repeat it here, except for four things:

1) Firstly, shit. John went to a grammar school where he became friends with children who lived in council houses. They had kitchens and flush toilets. John lived in a pit village with a “nettie” across the road: “Middens where you shit in a toilet, but it was basically pure shit, and once a week the midden men came and cleaned them out.”

2) White paint. One day John’s dad and his dad’s friends painted on the road “Vote for Labour, do it well, and let the Tories go to hell”. He says, “The Attlee government was the greatest reforming government for the working class in my lifetime. It took us from nowhere and lifted us out of, not poverty, but low wages, a simple life.”

3) Coal. One day John’s dad, a miner, took him to the pit to watch a ribbon being pulled: “This colliery is now managed by the National Coal Board on behalf of the people”. “It was something that he’d lived for all his life,” says John.

4) Profit. John started as an apprentice pit surveyor and worked his way up. Then he became a property developer. He made his first money renovating old cottages using a government grant and a NatWest loan. While he was working his way up, a friend in the welfare hall said: “You’re not one of us anymore; you work for profit.”

Next, Geoffrey Howe. In 1978, Geoffrey was the opposition spokesperson for Treasury & Economic Affairs. One night he made a speech at the Waterman’s Arms on the Isle of Dogs in London. The speech was titled ‘Liberating Free Enterprise: A New Experiment’. It was about deregulating areas of urban decay to encourage developers.

Geoffrey told the audience: “We cannot, I believe, create a rich society unless we are prepared to accept and welcome the fact that some people will, as individuals, become richer. Unless people are able to earn and keep significant reward for the investment and effort that we wish them to put into our urban deserts, they are just not going to be interested.”

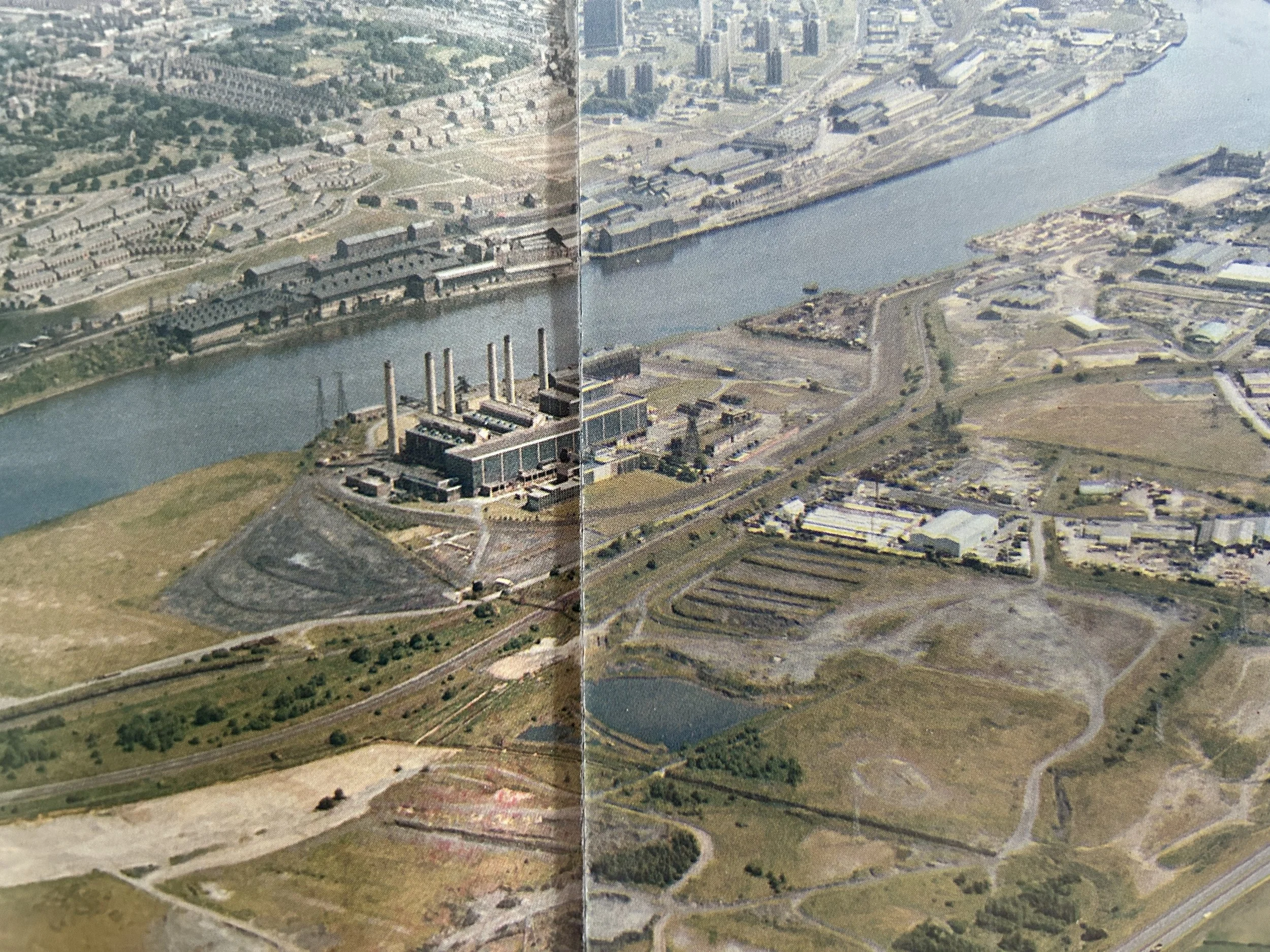

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, Geoffrey’s enterprise zones became policy and councils nominated potential sites. One chosen site was in Gateshead, a lagoon of ash and water that had been pumped from the power station at Dunston.

John: “I jumped in before everybody. It was basically freedom from everything. No taxes. No planning.”

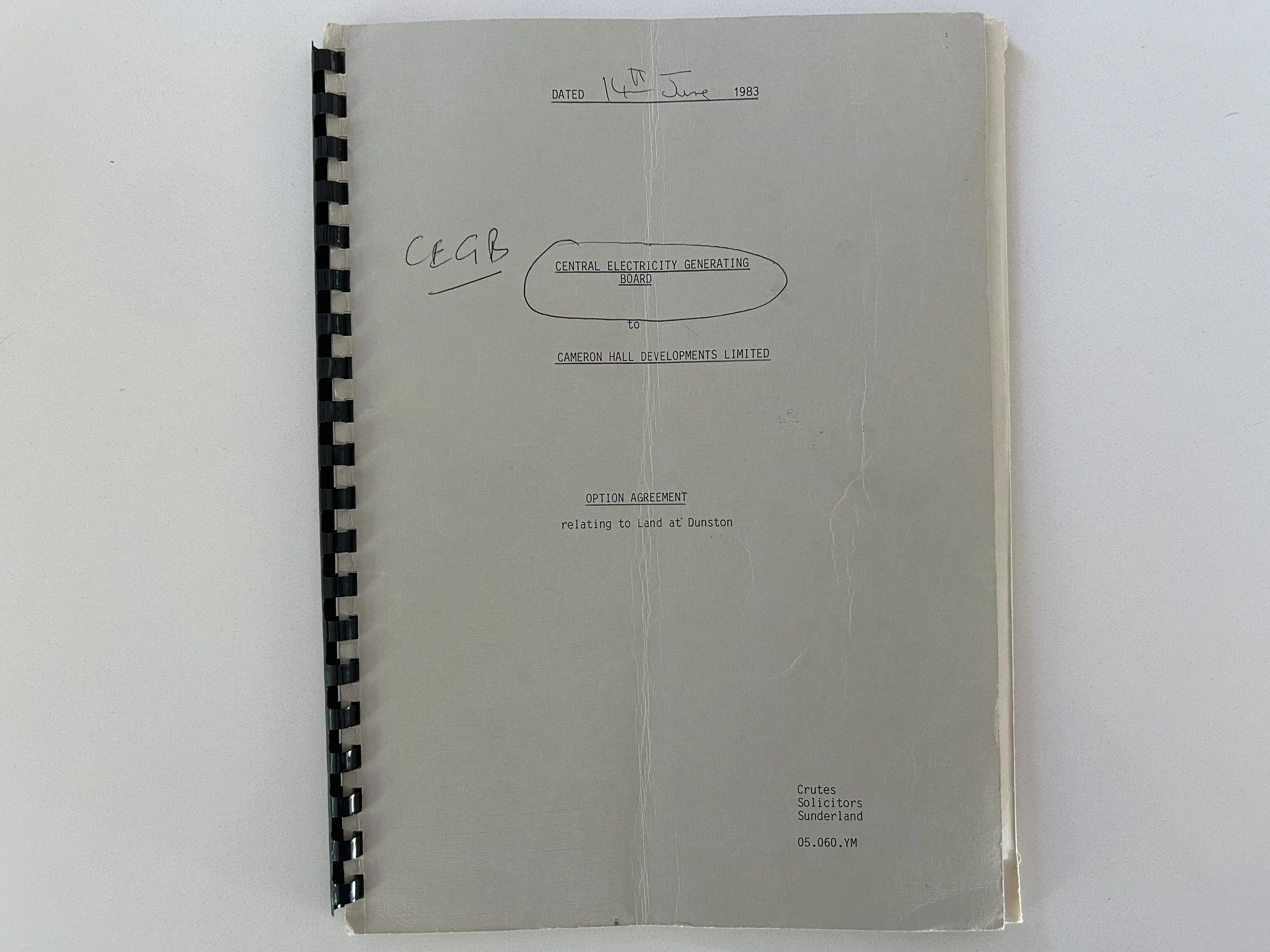

The option agreements are in John’s Aldi bag, both dated 1983. In one, John agrees to pay the Northumbrian Water Authority £130,000 for their part of the land. In the other, he agrees to pay the Central Electricity Generating Board £750,000 for the remaining land.

Next, he hired a contractor, Rush & Tompkins, who had an office in the North East. John wanted all the construction to be done by firms from the North East, or at least firms with an office in the North East.

A sign by the side of the Western Bypass read: “Built by North East people, for the people of the North East.”

Which is where suspended ceilings come in. Enjoy.

My dad’s been dropping his belongings off at my house recently. I think he’s preparing. There’s a will in one bag. There are wedding photos in another.

He’s also been emailing about his life: “we had a cat – everybody in salford had a cat to control the mice – we also had a small wash house where the mangle was and the poss tub and sink – outside was a yard with an air raid shelter that was now the coal bunker and of course the outside privy.”

One of the things he dropped off is an album filled with photos of suspended ceilings. My dad used to co-own a suspended ceilings company. He had vans and a yard in Heaton. There are photos of his van in the album.

But most of the photos are of ceilings: a private school’s swimming pool, Labour clubs, the Carrefour supermarket at the Metrocentre.

He wrote an email about that one: “This was an unusual size cell – made by form wood – normally cell sizes are 80 mm x 80 mm – so pricing the labour etc was a gamble – normally we priced on 3 margins – 15% to get it – 20% a normal mark up – 25% if we were assured of getting it – I decided to go in at 15%.”

My dad got the job and the contractor asked him to price the rest of the Metrocentre.

“I couldn't believe our luck – and so it began from carrefour to the hotel 5 years later and the office block and of course R AND T's demise – 5 years of entertaining – targets for completion – lots of profit – big cars – good wages – we thought it was never going to end.”

It was a boom time for my family. We went on holiday to a caravan site in France. We had meals out at Dante & Piero.

I ask my dad about the big cars and he says he’s not sure about my questions, meaning he’s not keen on them, but he replies that he upgraded the work van and got a Mercedes 200 to drive. I remember thinking people at school hated me because my dad drove expensive cars. Diddums.

It was always going to end of course.

Booms do.

Rush & Tompkins finished the Metrocentre and tried to become a property developer. The recession came in 1990 and they called in the receivers. They owed my dad money. My dad called in the receivers.

The vans went. The yard went. Jobs went. The Mercedes went. It was a grim time at home.

Dad’s stoic over email: “The metro centre years were fantastic – wonderful achievement for us and many good memories – but nothing lasts forever.”

I look through the rest of my dad’s belongings. There’s a gold-coloured invitation in one of the boxes he dropped off: “Cameron Hall Developments Ltd cordially invite Mr B Hankinson to be present at this memorable occasion.”

It’s for the opening of the Metrocentre.

I look through John’s Aldi bag. There’s a cassette recording from the opening event: “The Magic of the Metrocentre.”

I play it on my old hi-fi. There are interviews with John and politicians, then a woman sings: “You can reach out and touch / a dream come true / step into the future / it’s waiting for you / at the Metrocentre.”

There’s a souvenir newspaper supplements, produced by The Journal.

A letter on the front page says: “To dream the impossible dream is simple. To have the will-power, perseverance and sheer guts to make it a reality of concrete and glass, providing work and prosperity for hundreds of people, takes a determination few possess. John Hall believed so much in his MetroCentre dream that he has made it come true.”

It’s signed by Margaret Thatcher.

Over the page is an article by John: “When you look back at the area from say San Francisco, it makes you realise how small and insignificant the land mass of the North-East is, in global terms.

“The North-East is a village, this can be both a strength and a weakness; its strength lies in its people, warm and friendly; loyal and with simplistic honesty; its weakness in my opinion is that in general we are too introvert.

“Too often we live in our past glory which was at that time magnificent. The past now is history and we must learn from it but our future and that of children and grandchildren lies in tomorrow.

“The MetroCentre, is I believe, part of that regeneration.”

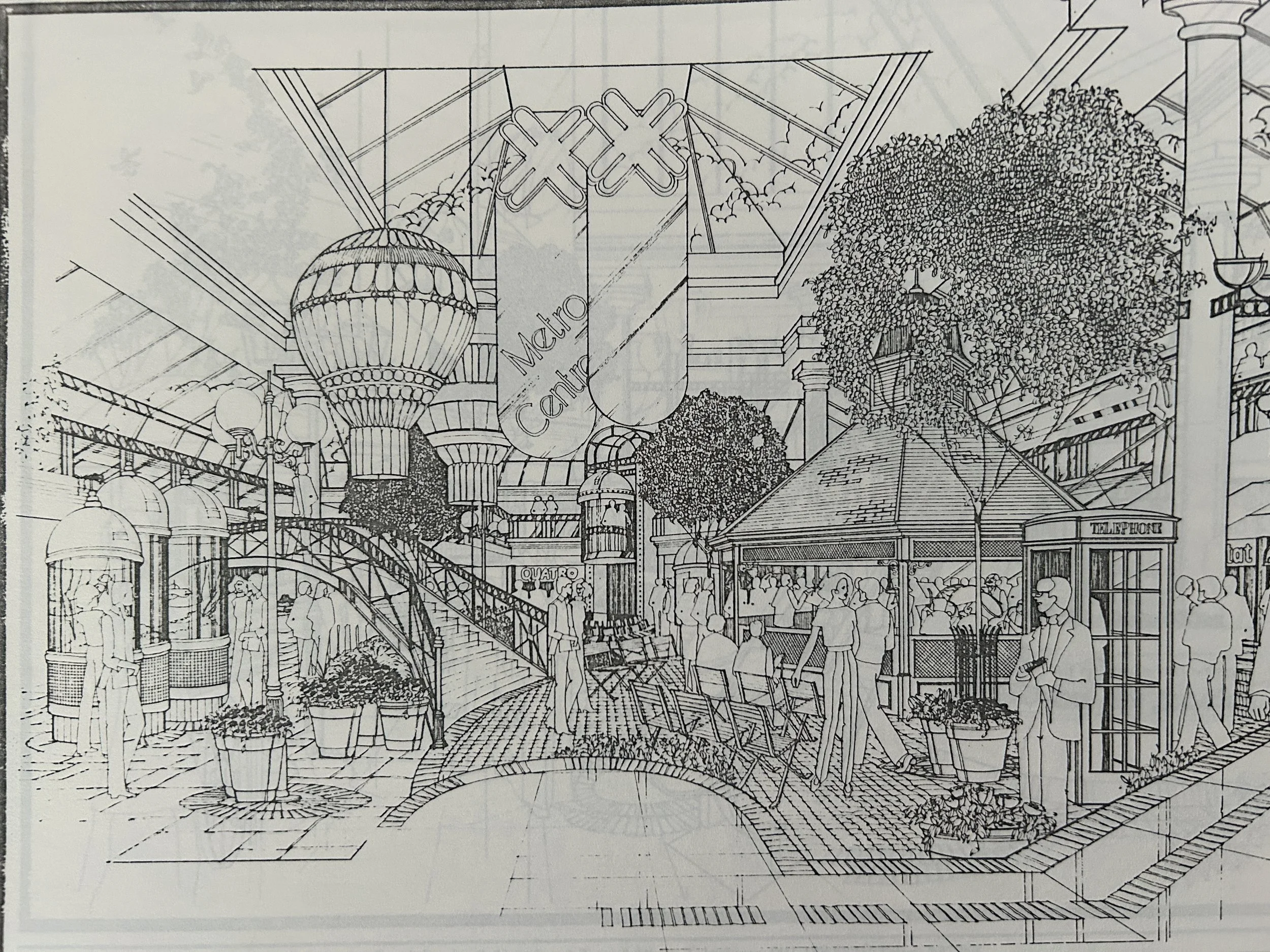

A brochure in John’s bag shows the Metrocentre when it first opened: glass lifts, fountains, old ladies on a bench, a barrow, a bandstand, parasols, streetlights, a town clock, a stone bridge over a pond with fake ducks.

I remember how green the Metrocentre seemed.

There’s a press release about the plants: ficus benjamina, ficus nitida, plumbago. It says John went to Florida to choose the plants. Christmas wreaths and garlands were shipped over from San Francisco.

Another brochure lists the restaurants: La Colonnade, La Piazza, La Terrasse, McDonald’s.

I’m not being snarky; it was exotic then.

Another press release says Newcastle and Sunderland footballers will attend the opening of Clockworks Food Court on separate days.

A note to editors says: “WHAT IS A FOOD COURT? Firmly established in the USA and fast gaining popularity in Europe…”

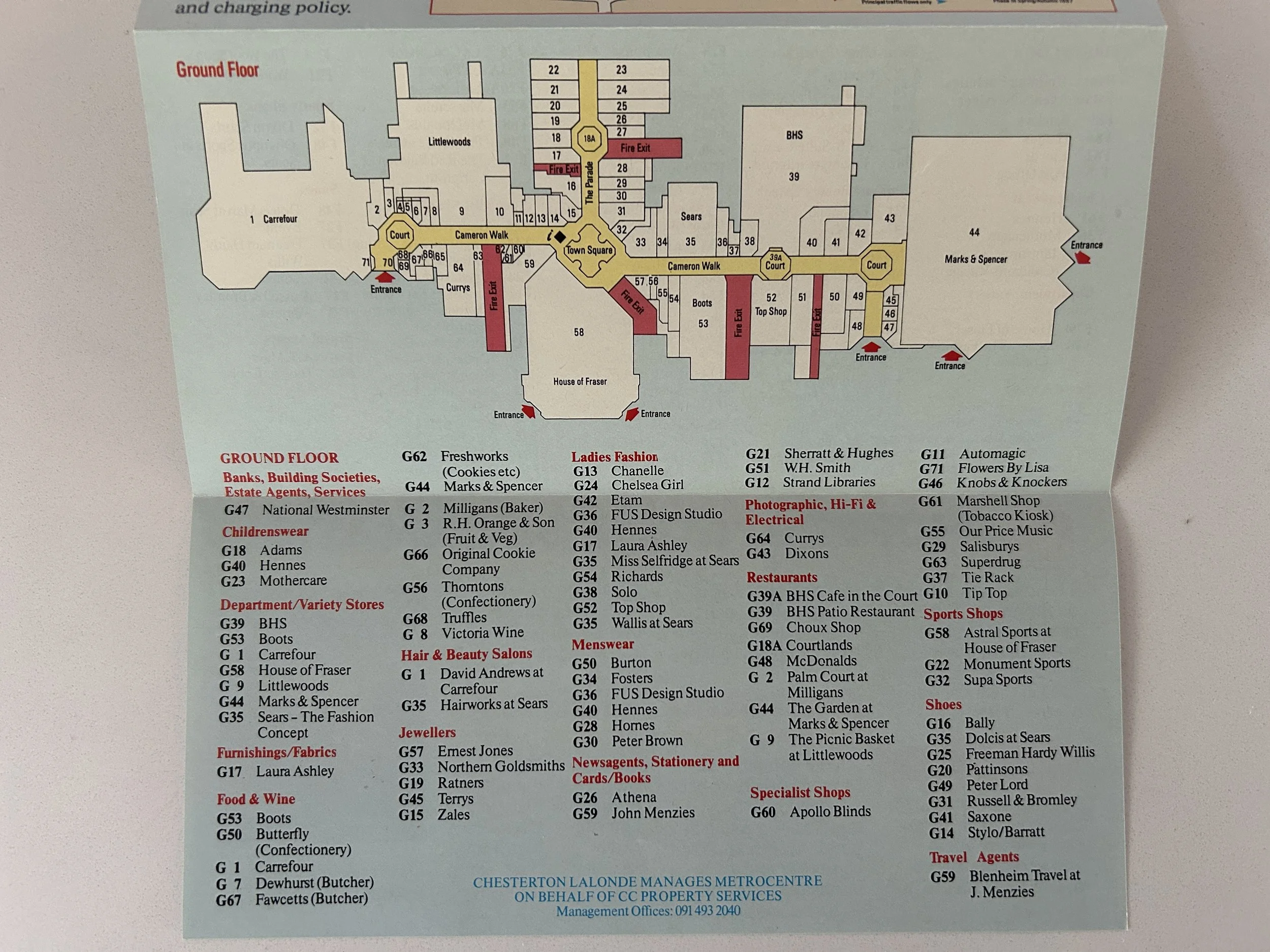

There’s a directory of all the new shops: John Menzies, Athena, Our Price, Sears, Victoria Wine, Monument Sports, Ratners, Mothercare, BHS, Littlewoods, Warehouse, Thomas Cook…

They’ve all disappeared of course.

I don’t know when the Metrocentre started to sink.

Maybe sink is the wrong word. An engineer told me the council carried out experiments on the ash before the Metrocentre was built, to see if the land was stable enough.

They made ash piles, six metres high, which you could see from the road as you drove past.

The experts watched how the piles behaved – or how they consolidated over time, as the engineer put it – and decided it was okay to build on.

The ash was spread over the site. Heavy plant, the machinery kind, was used to compact it.

Construction began in areas where the experiments had taken place, but those were areas where the underlying ash had had a long time to compact and drain, because it was used for those experiments.

When construction started in other areas, the underlying ash had had less time to compact. The drainage wasn’t as good. It took years, but it was no surprise when the building started to crack.

The Metrocentre was moving.

They started to monitor the movement, which was affected by tidal levels, ground temperature, how many cars were in the car park, how much stock the shops had in.

To fix it, they dug shafts from the periphery underneath the building, then put pipes in the shafts and pumped 350,000 litres of grout in under the Metrocentre.

That was in 1999. In 2002, they added another 325,000 litres.

Now the Metrocentre rolls as one entity, like an oil tanker.

And now the end, which is also the future. It starts in 1988, when a documentary called The Kingdom of Fun was broadcast by the BBC. You can see it on YouTube.

It has a voiceover: “Tyneside was once the source of much of Britain’s wealth. Today it is a byword for industrial decline. But two years ago, in the midst of this wasteland, a brave new world was built.”

The film shows Frankie Howerd in a toga, opening the Metrocentre’s new Roman Forum.

It shows Margaret Thatcher in a glass lift before the 1987 election.

A security guard talks about his low wages and says people use their Access cards to pay for shopping.

A rollercoaster zooms around Metroland Funfair. I loved that rollercoaster. It felt like we had something.

The documentary-maker interviews T. Dan Smith, a miner’s son who became a politician and championed the regeneration of the North East. He also went to prison for corruption in the 1970s.

In the film we see him on a grassy hill, the Metrocentre behind him, saying that anyone who claims the Metrocentre will contribute to regenerating the North East is “telling fairy stories”.

Dan: “These kind of leisure industries, they can make a contribution if you like to superficially… back to the pantomime. If you have a few pints and you feel happier, the world’s a better place, but tomorrow you’ve got a headache.”

The film shows John in the Metrocentre telling the documentary-maker that the main thing is we built the Metrocentre ourselves, and provincial regeneration will happen because people here want it to happen.

“We will create, in a sense, the new North East out of the ashes of the old,” he says.

The documentary maker is Adam Curtis.

He’s famous now. People around the world watch his documentaries looking for answers.

I’m looking for answers, so I phone him.

I tell him I don’t think the Metrocentre took us anywhere but nobody knows what to try next.

Adam: “Have you noticed that? There is no-one with a story about the future.”

He asks why I’m writing about the Metrocentre.

I tell him I get frustrated, because when people write about the North East they often write about coal and ships, but those things are nothing to do with my life, and they make the North East feel like an unfamiliar place to me.

So I’m writing about the thing that replaced them: shopping.

I ask why he made his documentary.

Adam: “I was saying, ‘Look, what I really think about this country at the moment is that people’s real job is no longer to work in offices or factories. People’s real job is to go shopping.’ They’re called ‘bullshit jobs’ these days, but what is called your job is actually a way of earning the money to go shopping, which is your real job.

“I remember I wrote a whole section of commentary all about this and the BBC just weren’t interested. They said, ‘That’s silly, Adam’. But I sort of think, looking back on it, I was probably right.”

He asks about how the Metrocentre is now.

I tell him the Church Commissioners, who bought it from John, sold 90 percent to Capital Shopping Centres, who used debt to buy it.

They closed Metroland, renamed themselves Intu, and told us to call it the Intu Metrocentre. They issued a £485 million bond on the centre’s debt. Coronavirus came. Intu entered administration.

Adam: “In a way it went through the same narrative arc that we all went through, which is we borrowed lots of money and got highly indebted, and it all crashed in 2008, and so they got trapped by their debt. The story of our time is debt rather than production.”

He says he thinks people were getting bored of shopping regardless of the internet. He asks if the Metrocentre was quiet before the lockdown.

I tell him I’m not sure, then phone a woman called Deanna who sold Kat Von D make-up in Debenhams at the Metrocentre.

I tell her I won’t use her full name.

She says it was getting quieter for a while.

Deanna: “I remember first starting in cosmetics, and Christmas was completely booming, with a lot of figures being thrown around. If I compared it to last Christmas, it wasn’t great.”

Deanna collected her belongings from work yesterday. Debenhams won’t be reopening.

I ask Adam whether, as an outsider, he has any ideas for what we do next.

He says he’ll go for a bike ride and think.

A few days later he calls back.

If you’ve seen his documentaries you’ll have an idea of what he says, so I won’t repeat it here, but I also don’t want the things he told me to exist only on a flash drive in my desk drawer, so I’m including four points.

1) “T. Dan Smith represented something quite big, I think is what I felt at the time. It was the end of that kind of idealism, which told you a story about the future they were going to build, because the future they built was corrupt and pretty horrible.”

2) “What Hall built was a lovely space where you could come in, borrow money and just dream. It didn’t change anything. It didn’t develop into anything. It was quite a static system.”

3) “Then it sort of began to decay in 2008, and why we find it so difficult – this is really pretentious – why we find it so difficult to deal with catastrophes today, whether 9/11 or Covid, is we have lost the capacity to tell ourselves stories about the future. We find ourselves trapped in the past in this present as individuals, like being lost in Metroland all on your own, and it’s very frightening, because there is no picture of how we can get out of it.”

4) “We’re going to have to start thinking of some stories soon.”